Jacqueline de Jong’s Erotic and Radical Vision Arrives in Switzerland

Jacqueline de Jong’s bold, erotic, and radical vision arrives in Switzerland, an uncompromising retrospective of a fearless artist.

This autumn, the Kunstmuseum St. Gallen opens a remarkable chapter in Swiss cultural history with the first-ever retrospective in the country dedicated to Jacqueline de Jong.

Spanning over six decades of provocative and fiercely independent work, the exhibition offers not just a survey of her oeuvre but a deep dive into an artist whose career defied convention at every turn.

Born in Hengelo in 1939 and passing in Amsterdam just last year, de Jong's name may not yet carry the household recognition of some of her contemporaries, but that is beginning to change.

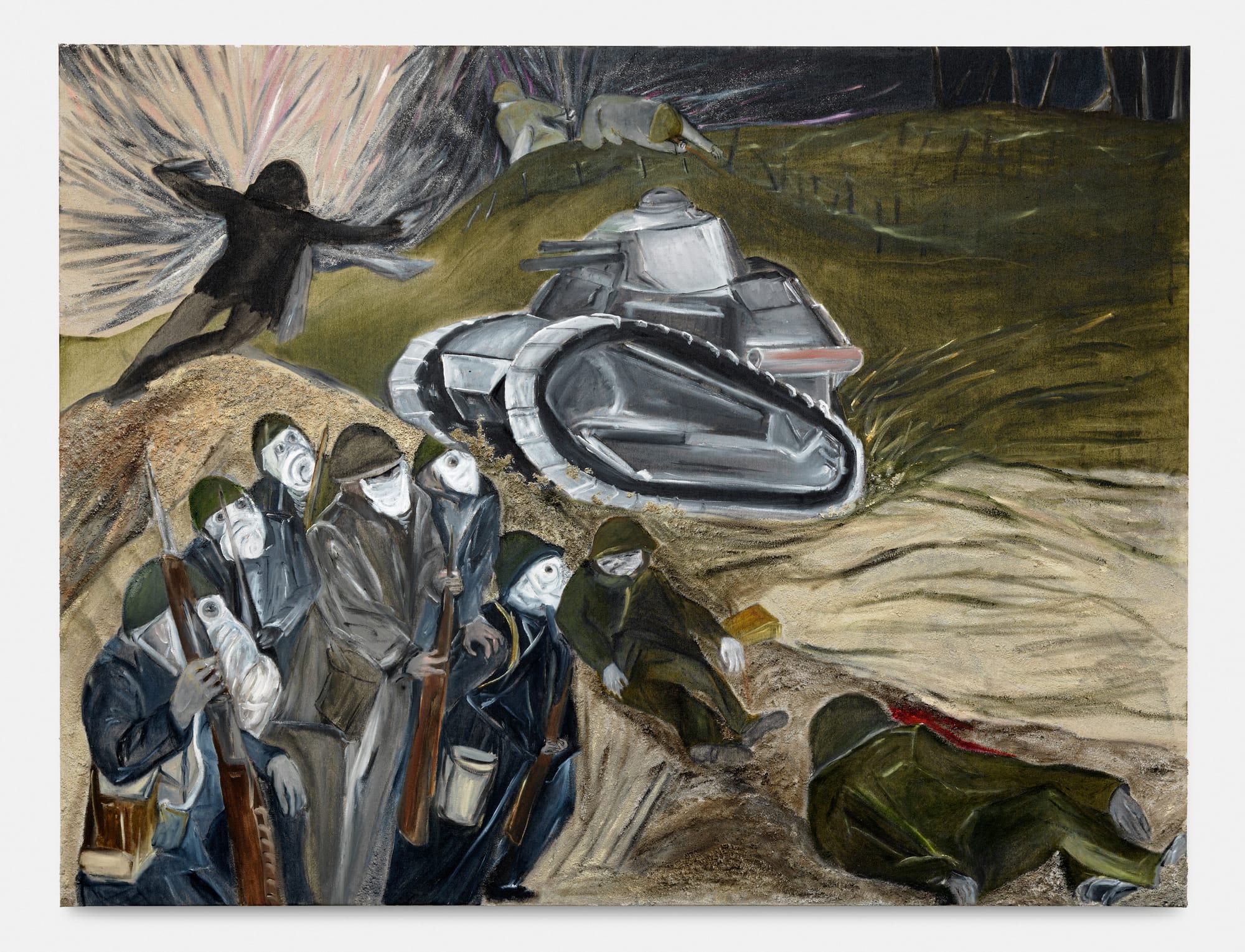

A committed member of the Situationist International at just 21, she was steeped early in a revolutionary milieu that sought to liberate life from the strictures of capitalism, spectacle and conformity. That spirit of subversion never left her.

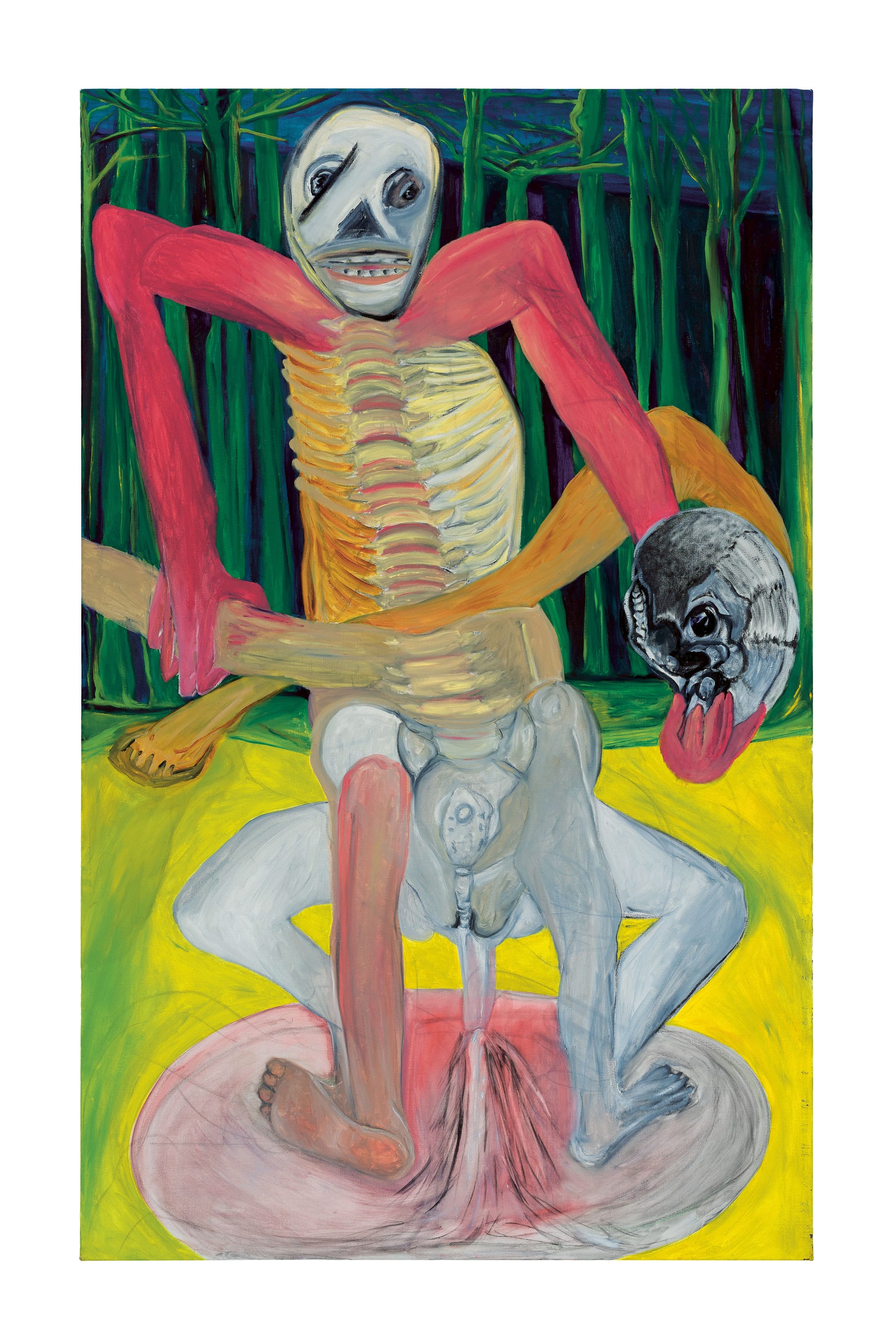

What emerges in this retrospective is an artist who never sought safety in style. From the raw immediacy of her early works to the lush sensuality and biting wit of later pieces, de Jong embraced contradiction.

Her work is political without sloganeering, erotic without cliché, and playful without surrendering to whimsy.

The exhibition draws together around 100 works, traversing painting, sculpture and print, organised thematically into six sections: Chaos, Popular Culture, The Everyday, Play, Politics and Editor.

Each section invites the viewer to confront the layered, often dissonant realities that de Jong refused to simplify.

There is a visceral, at times anarchic quality to her visual language. Rather than aestheticising the political, de Jong embedded her politics within form itself, jagged, muscular brushstrokes, recurring grotesques, and a relentless questioning of the image.

Yet amid the darkness, there is humour, erotic charge, and a perceptible joy in the act of disruption.

That her first major Swiss exhibition should take place now, in the wake of her death, is poignant. It is also fitting.

De Jong was no stranger to the country: her mother was Swiss, and Switzerland served both as refuge during wartime and as a creative retreat in her adult life.

Her links to Ascona, Zürich and the Swiss art scene were enduring, yet it has taken until now for an institution to place her centre stage.

Melanie Bühler, curator of the exhibition, has constructed a show that captures de Jong’s shape-shifting brilliance without taming it.

Visitors are not guided through a career arc so much as drawn into a universe where meaning is unstable, where pleasure and violence co-exist, and where resistance is a way of seeing.

Accompanying the show is a substantial bilingual catalogue published by JRP|Editions, featuring new essays and an unpublished conversation between de Jong and cultural theorist McKenzie Wark.

It is a vital companion, but one suspects de Jong would have wanted viewers to stand before her work without a net, to look, to feel, and above all, to question.