The Rolls-Royce Phantom Stole the Art World’s Spotlight

For a century, the Rolls-Royce Phantom has carried icons and inspired art, becoming both canvas and catalyst for creative legends.

There are luxury cars, and then there is the Rolls-Royce Phantom. For one hundred years it has not only transported cultural icons but has also played an active role in their creative worlds.

From its debut in 1925, the Phantom has been a moving room, a travelling salon and a private stage on which the world’s most vivid personalities have performed their lives.

Salvador Dalí used one to transform the streets of Paris into a surrealist performance. Andy Warhol made one part of his mythology. Dame Laura Knight painted from hers at English racecourses. In each case, the Phantom was not a silent accessory but an accomplice in creativity.

In the winter of 1955, Paris witnessed a spectacle that even the avant-garde could not have imagined. Salvador Dalí, in the city to give a lecture at the Sorbonne, borrowed a friend’s black and yellow Phantom. Into its rear compartment he loaded five hundred kilograms of cauliflowers.

The car moved through the streets like a surreal procession. When Dalí arrived, he opened the doors and sent the vegetables spilling across the frozen pavement.

Inside the lecture hall he spoke on “Phenomenological Aspects of the Paranoiac Critical Method”, yet it was his arrival in the cauliflower-filled Phantom that was remembered.

Dalí’s connection with the Phantom was more than a single act of theatre. In 1934 he depicted the car in Les Chants de Maldoror, showing it stranded in an icy wilderness. The image fused mechanical elegance with dreamlike desolation, capturing the surrealist instinct to combine opulence with the unexpected.

A decade later, during his autumn and winter residencies at New York’s St Regis Hotel, Dalí met the young Andy Warhol. Their encounter, captured by photographer David McCabe, was a study in contrast. Warhol appeared cautious while Dalí held court with theatrical command.

Where Dalí had borrowed his Phantom, Warhol would eventually own one. His was a 1937 model that had been converted into a shooting brake after the war.

He discovered it in a Zurich antique shop in 1972, bought it immediately and shipped it to New York. For six years it was part of his personal life, as much a fixture as the silk screens and silver wigs that defined his public image.

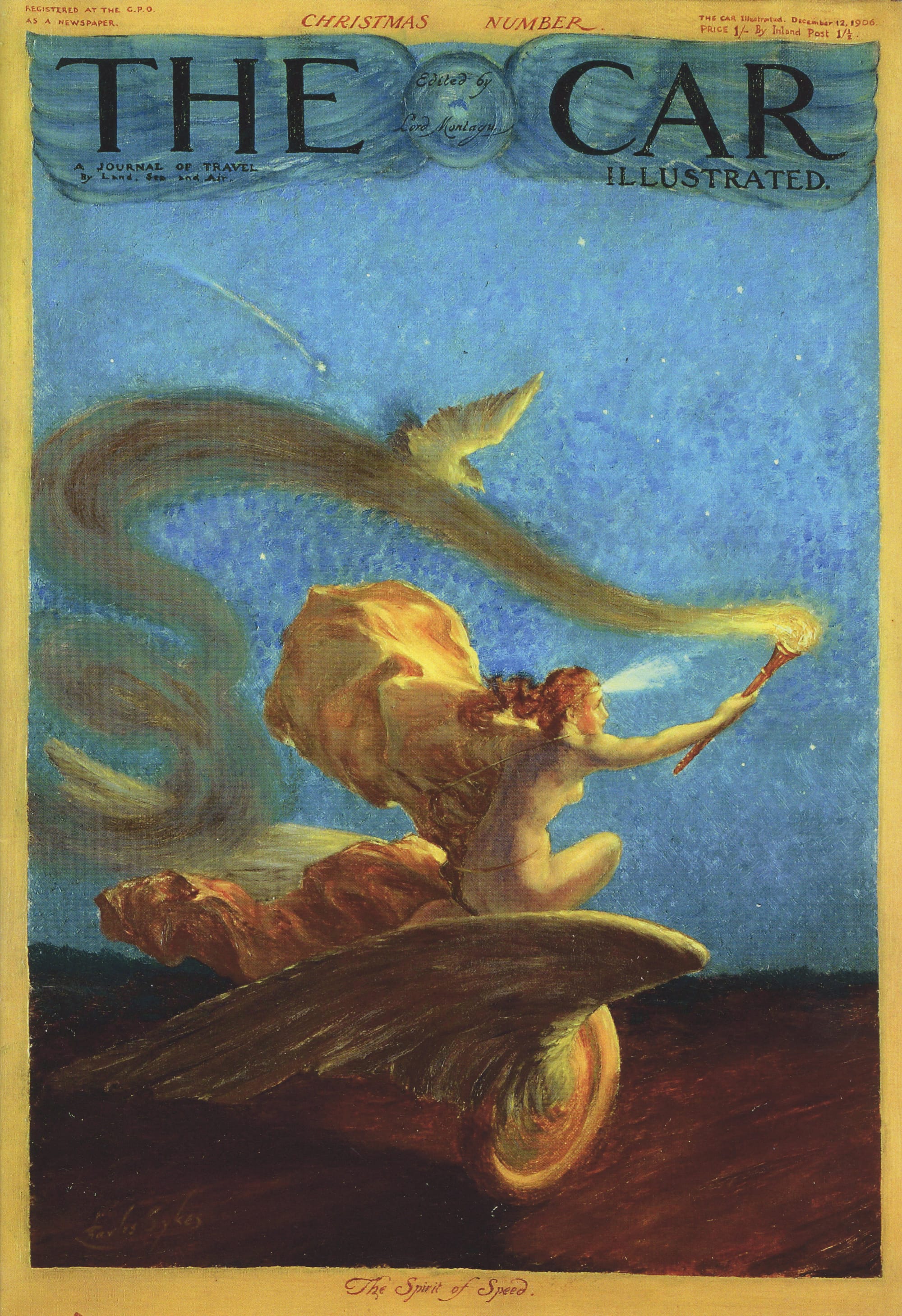

Well before Dalí or Warhol brought the Phantom into their circles, Rolls-Royce had already embedded art into its identity. In 1911 Charles Sykes, a painter and sculptor trained at the Royal College of Art, created the Spirit of Ecstasy.

Partly inspired by the ancient Greek Winged Victory of Samothrace yet softened into something more ethereal, the figure captured the sensation of motion so refined that even a delicate form could ride the bonnet without losing balance.

For decades each mascot was hand-finished under Sykes’ supervision and later by his daughter Jo. Many early Phantom owners unknowingly carried a Sykes original at the prow of their cars.

Across eight generations the Phantom has remained more than a symbol of prestige. It has been exhibited at the Saatchi Gallery in London and the Smithsonian Design Museum in New York, not only as an automobile but as a work of art.

Its lasting appeal lies in its ability to be both a canvas and a catalyst. It is a meeting place for engineering precision and artistic imagination.

For the century past and the century to come, the Phantom offers those who enter it something beyond transport: the opportunity to add their own chapter to its remarkable story.